[8] Falling & Loving

In other words, the personal “art coefficient” is like an

arithmetical relation between

the unexpressed but intended and the

unintentionally expressed.

—Marcel Duchamp2

1

The old custodian came into the gymnasium as I was trying to figure out what all the contraptions were for, and I asked him if he knew. “I just sweep in here whenever some event is going to happen,” he said. “What do you suppose these are for?” I asked again, pointing to the cords hanging down from the platform overhead. “The cords are fastened,” he said, pointing up to the dozen or more little hoppers, “to those buckets up there and when they pull on the cords all sorts of material is going to fall.” “Like what?” I asked. “Like confetti,” he said, instinctively moving out of the way, “and peanuts, maple syrup, molasses, flour, milk, honey, sugar, popcorn, and mylar, they say.” Two (or maybe there were three) bowling balls were hung on cables or ropes. He pushed one of them, like a tether ball, and it swung back and forth pendulum style. “I heard,” he said, solemnly, “that the dancers have to dive and race through that little space at the perigee where the arcs of these swinging orbs threaten to intersect.” “Timing would be everything,” I added.

when an osprey drops

feet first from the sky, like a bomb

talons sharply out

the impact’s ostentatious

rising phoenix with its prey3

danger as an art

requires us to savor fear

though dodging outcomes

at the very last minute

anyone can hit the wall

it is the moving

around confirms the human

kinesis as life

animals swim, fly, and run

even the trees hold on tight

2

Choreographers use many tools to create and record dances. The moves and gestures, arising out of the body’s spontaneity or the brain’s analysis, drift away like smoke as soon as they occur, unless some means is used to “record” them. One dancer creates moves as she goes, in thin air, and all we can do is rush to write or draw pictures of what we saw or record the motions in the codes of various dance notation systems.4 Another dancer cogitates, imagines, and creates steps and motions, literally out of thin air, and writes them out for live dancers later to perform. The mystery of choreography resides, however, in questions about just how and why the dancer for the first time ever raised her right arm just so, then bent and twisted her torso in that way, or kicked high with her right leg...and just kept on going, pushing the dance in the imagination ahead of her while the dance already danced trailed behind in fading images, like the dragon at Chinese New Year.

drawings do provide

hints approximating dreams

choreographers

have about flying dancers

but they leave out the motion

you can only hint

with the use of curving lines

what you want to say

she flies on his outstretched arms

while escaping gravity

does his arm move first

or the image in his head

does he know just when

to start and stop or does he

wait to see it on paper?

3

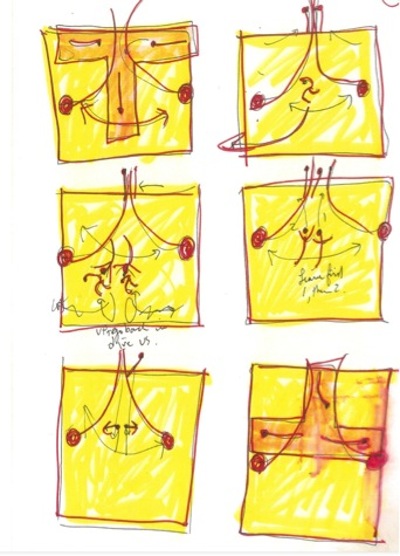

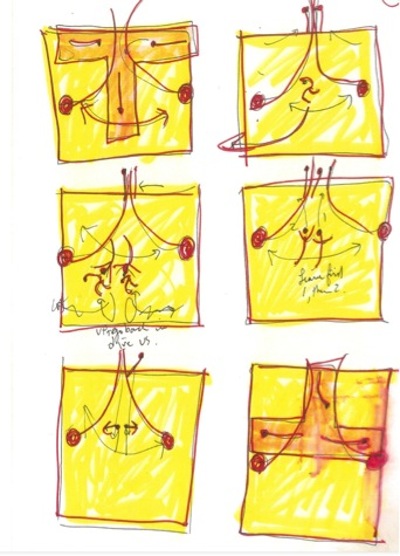

Step back, now, and forget ideas of purpose or utility and consider the pictures above as pictures in their own right, as a work of art. Or, rather, see it as a composite work of art—drawings or a painting, on the one hand, made up of six abstract panels AND, at the same time, pushing past the idea of an inexplicit pattern of line, shape, and color, see it as a representation of an imagined dance. The dance abstracted, the abstraction dancing. What do you see when you peer deeply into a red and yellow window by Matisse, beyond the suggestion of some person, say, or the sea? You can’t help but see the underlying geometry, the space and shapes, colors and arrangement. So, here, beyond the idea of dance motion, interaction, and time, is a yellow space, red lines, and stick figures, embodying the artist’s multi-valenced urgency at the time.

say the hardest thing—

art is indeterminate

count off the factors

intention, form, genre, line

and color, just don’t step back

too far, then things bleed

the edge into the center

a sympathetic

eye becomes a crude dollop

smudged with the edge of a thumb

imagination

finishes everything up

following the urge

from blurring gradually out

to the sharp “smack!” on the floor

Bio: Charles D. Tarlton

MacArthur “Genius” Award-winner Elizabeth Streb has dived through glass, allowed a ton of dirt to fall on her head, walked down (the outside of) London’s City Hall, and set herself on fire, among other feats of extreme action. Her popular book, STREB: How to Become an Extreme Action Hero, was made into a hit documentary, Born to Fly,

directed by Catherine Gund (Aubin Pictures). Streb founded Streb Extreme Action in 1979. In 2003, she established SLAM, the STREB Lab for Action Mechanics, in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. SLAM’s garage doors are always open: anyone and everyone can come in, watch rehearsals, take classes, and learn to fly.