|

KYSO Flash ™

Knock-Your-Socks-Off Art and Literature

|

|

|||

Painting With Words: The Art of Haigaby Jack CooperTwo years ago, my wife, Kazuko, and I visited a single museum dedicated to a Japanese haiku poet named Kaga no Chiyo-jo.1 In the West, such a museum would be crammed with books, writing nooks, letters, photos, and memorabilia—Frost’s Stone House in Vermont, for example, and all three of Pablo Neruda’s houses in Chile. But words projected on the floor in colored lights? Poems embedded into artwork and hung on the walls? Verse carved in stone at the entrance to gardens? Such is the way poetry is often treated in Japan—as another visual art. After all, Japanese writing itself, ultimately pictorial like Egyptian hieroglyphs, is regarded as its own art form. Little schoolchildren still practice writing Japanese and Chinese characters with brush and ink. In Kanazawa on the eastern shore of the Sea of Japan, one can tour an entire gallery devoted to Japanese calligraphic handwriting, where visitors ooh and aah at the skills exhibited in sumi-e, or ink wash painting. Many of the works include wispy black and white images of birds, rivers, mountains, and clouds made with the same brush as the calligraphy.

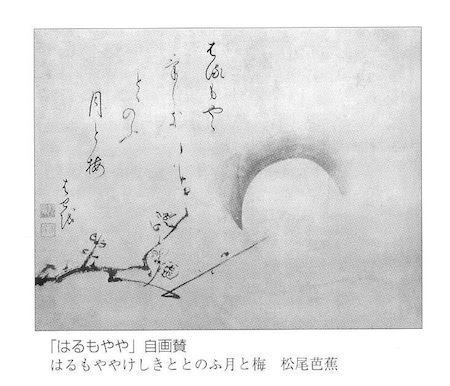

With words being art to the Japanese, it’s not surprising that Haiga, the combining of words and images in a single work, is commonplace. The form first arose in Medieval Japan (1185–1600), a period in which the emperor mostly served as a figurehead, and aristocrats and samurai warriors became the de facto rulers of the land. Made famous by haiku masters Matsuo Bashō (1644–1694) and Yosa Buson (1716–1784), haiga became a common pastime among aristocrats during the Edo Period (1603–1868) when the country was under the control of the renowned Tokugawa shogunate.

Haiga is often translated as “haiku painting,” most likely because it started out that way, but also, there is the practical matter of space. Longer forms may contain too many words and distract from the simple beauty of the painting, simplicity and subtlety being the core of the Japanese aesthetic. Picture the sublime Zen garden at Ryoan-ji Temple in Kyoto: nothing more than sand and a few shapely boulders. If the West was a late-comer to painting with words, perhaps because our ABCs are not inherently artistic, we quickly made up for lost time. In the last 150 years, words have been embedded in everything from abstract art, collages, and posters, to advertising, wall calendars, monthly planners, and even T-shirts. Starting with Issue 5, KYSO Flash has published two dozen haiga in good ol’ English. Witness the loveliness of Alexis Rotella’s Solstice from Issue 9. And the power of ordered by Janet Lynn Davis in Issue 6. (The complete list appears beyond the footnotes and references below, under Links to KYSO Flash Haiga.) In crafting haiga, one could do worse than start with the traditional Western haiku form:

Here in KYSO Flash, you will notice that effective results can also be obtained with fewer syllables and lines, or even more than, reminding us that breaking the “rules” is one of the identifying features of true art. Many poets, past and present, also drop the seasonal aspect of their haiku, replacing it with the human comedy in a related form known technically as senryu. In traditional haiga, it’s typically the seasonal aspects that unite the two art forms, although the relationship between the words and the painting does not have to be clear, can be understood as contrasting, or may allude to elements of the drawing that can’t be seen, such as the implied sounds, as in coolness (Buson’s bell poem5), and the more famous “frog pond” by Bashō:

We clearly see that frog and the pond, whether it’s painted or not, but the haiku is there to remind us of the sound. Of course, neither haiku nor haiga contain actual sounds, or aromas, or temperatures, or wind, or visible movement. Human imagination is always there to fill the void. If a complete representation of reality is what we want, perhaps we need to look to holograms, videos, and virtual reality, or, better yet, a walk in the woods. Footnotes:

Additional References:

Links to KYSO Flash Haiga: Issues 5 thru 11Janet Lynn Davis: ordered George Digalakis and Gary S. Rosin: This bird stands ready J. R. Lancaster and Gary S. Rosin: The shade of a dog Michel Lucas and Gary S. Rosin: Mist on the Moor Michel Lucas and Gary S. Rosin: Tranquility in White Michael and Karen McClintock: dandelions Michael and Karen McClintock: enough is enough Michael and Karen McClintock: for big fat radishes Michael and Karen McClintock: one bird Michael and Karen McClintock: we hear grunion P. A. Milton and Jack Cooper: Eleven Lines P. A. Milton and Jack Cooper: Tree Katherine Raine and Sheila Sondik: Plumage Gary S. Rosin: A ladder of light Alexis Rotella: Not speaking Alexis Rotella: Snowy owl Alexis Rotella: Solstice Alexis Rotella: Three Haiga: Insomnia; Poetry Break; and Sunday afternoon Debbie Strange: Four Haiga: in my hope chest; peeling paint; snowswept; and they called us Christine Taylor: prepping

|

|

Site contains text, proprietary computer code, |

|

| ⚡ Many thanks for taking time to report broken links to: KYSOWebmaster [at] gmail [dot] com ⚡ | |